Fourteen Years; Fourteen Minutes

A reporter reflects on the emotional challenges of writing about death

I have never been on this street before. I follow the small black Toyota onto the car-choked road and pull into a weathered driveway. I pull out my pen and reporter’s notebook and take a deep breath.

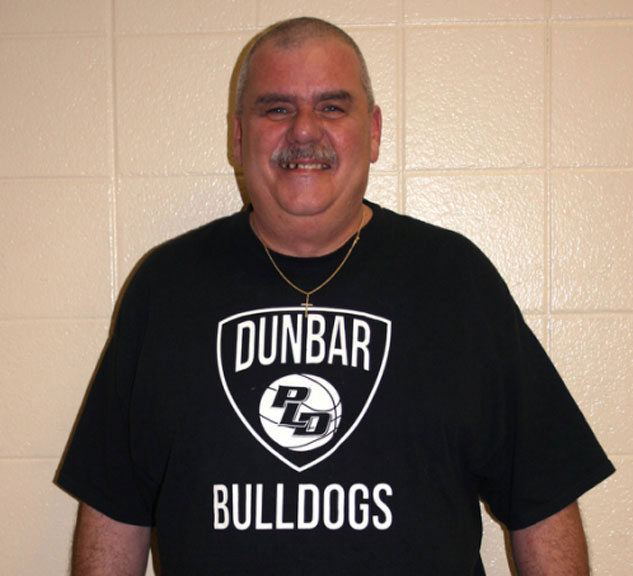

Dunbar English teacher, Mrs. Cynthia Jones, and I walk up to the front door and wait for about five minutes before she receives a text giving us the code on the door lock. We walk inside. The hallway is dark, leading immediately to stairs on the left. At the top is a man, barefoot and wearing pajamas. I now understand why he had asked me not to bring my camera, not because he looked unhealthy, but because he looked tired. He wheezed and I could tell that he was struggling to move.

We climbed the stairs, and she gave him a hug and then left to put a meal she had brought him into the kitchen. I shyly shuffled over to a chair facing his bed. He turned toward me, muting the home improvement show he had been watching. I told him that I was a reporter from the Dunbar Lamplighter and that I was very glad to finally meet him. Even though I carried a pen and notepad, I asked if I could record the conversation on my phone. He agreed.

I have written about death before, but this was different. In my sophomore year, I wrote an article about a boy named Jaleel Raglin who had been shot and killed. The purpose of the article was to record his father’s response to what he saw as a growth of violence in Lexington as well as the creation of a foundation in honor of his son. I was assigned the article post-mortem and the conversations I’d had with his father were over the phone. It wasn’t really personal. The interview with Bob, though, was personal. I hadn’t spent time with a cancer patient since I visited my aunt several summers ago. I wasn’t there when she died last winter, and I wasn’t able to say goodbye. It felt strange to think of her while interviewing a man whom I had never met, but it also brought me closer to him. I focused my questions on his life, not his impending death, and as we talked I almost forgot that he had a terminal illness.

When the interview was finished, I took the recording and my notes to staff writer Maggie Davis, to whom the article was assigned. Although I only conducted the interview and did not actually write the article, sharing his story impacted me in ways I never imagined. When the printed newspaper arrived, I was so proud of Maggie, and we were both excited to send him a copy. We heard back through Mrs. Jones that he enjoyed reading it, and that it brought a smile to his face.

Several days ago our Lamplighter adviser, Mrs. Wendy Turner, pulled me aside to tell me the news that Bob had passed away. I stood with Maggie as Mrs. Turner showed us how to leave a short message on the funeral home’s website if we wanted. Tears welled in my eyes, but they never ran. It didn’t seem real. Later, I pulled up the obituary website thinking of what to write. I barely knew him, but he had so much hope for Dunbar and this made me appreciate this school on a different level. Most students and teachers seem like they are just trying to get through year after year, so to have such a positive message coming from a man who knew he was about to die made me stop to think about why I hadn’t seen what he had. I couldn’t think of anything to write, so I shut my laptop and tried not to think about it. It wasn’t until 11:30 that night that I started to cry, grieving for his family and for those who knew him better than me.

Fourteen years he was here and all I had was a fourteen-minute interview. I regretted that I had wasted my chance to get to know him, and I began to think about others in the building I hadn’t thought about before—people who have so much to offer, but who are often in the background. During the interview, Bob emphasized that he felt respected by the staff here at Dunbar. He never felt that custodians were treated with less respect, and over and over again as he reminisced about his time as an employee, he described a job—and the staff and faculty—that he loved.

As I think about my own priorities and my goals, I will stop to remember Bob’s story. It is often said that no one on their death bed wishes that they had spent more time at work, but instead wish that they had spent more time with family and friends. For Bob, it appeared that he combined the two, and he had no regrets.

I'm obsessed with manatees.

Emily Liu • Jan 12, 2015 at 2:58 AM

Wow! This is really touching to read.