Student Voices, New Voices

The “New Voices” movement has been passed in 14 states and is proposed in 11. Could Kentucky be next? Student journalists around the state are optimistic.

New Voices legislation aims to give greater protection against the censorship of school-sponsored publications and news sites. Currently, 14 states have enacted these laws: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

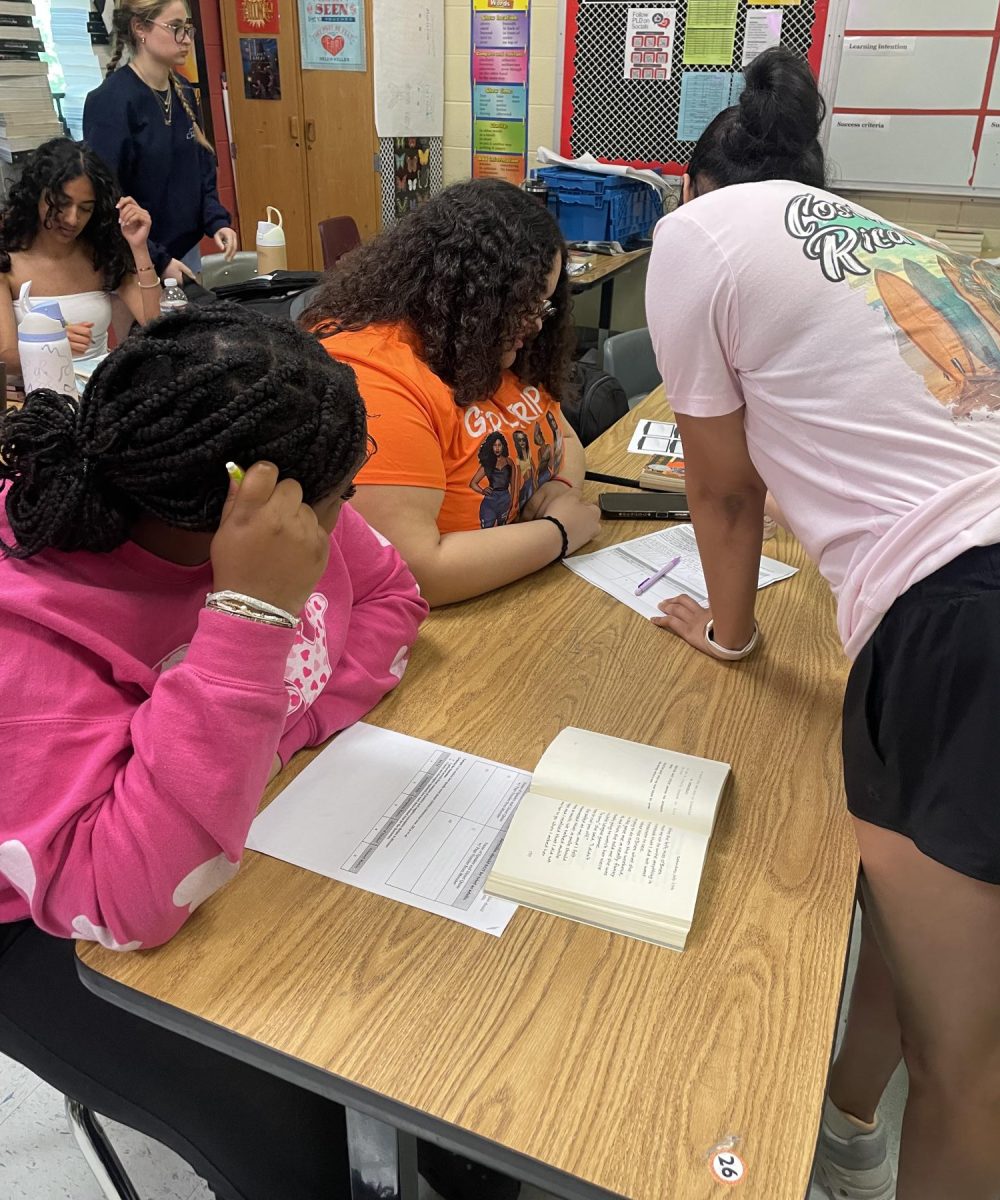

Student journalists can find themselves at the whim of administrators who ask them to take down stories they deemed to be “disruptive to the school day,” but how is that defined? And why don’t students have a First Amendment right to freedom of the press?

In 1988, the Supreme Court allowed K-12 administration to censor school-sponsored publications. The decision in Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier is considered a landmark case for student rights because it allowed public school administrators to censor articles that they did not think were appropriate.

Many student journalists, however, are hoping for greater freedom with a grassroots movement called New Voices.

According to the SPLC (Student Press Law Center) “New Voices is a student-powered nonpartisan movement of state-based activists who seek to protect student press freedom including advocates in law, education, journalism, and civics to make schools and colleges more welcoming places for student voices.”

The Jan. 31 meeting at DuPont Manual High School was attended by Lamplighter staff members as well as other stakeholders for New Voices Legislation.

In addition to the 14 states already implementing New Voices, Pennsylvania, Missouri, New York, and Hawaii are also preparing to present bills to protect the First Amendment rights of student journalists.

Kentucky, however, has not made as much progress.

In 2009, KY House Bill 43 failed to be passed. A former PLD Lamplighter staff reporter, Alex Riggs, wrote an article addressing the legislation soon after.

“Introduced by Representative Brent Yonts, House Bill 43 is intended to apply the [First] Amendment to all high school public forums allowing those students to practice the rights of free speech and freedom of the press,” wrote Riggs.

Riggs also interviewed Dunbar’s principal at the time, Anthony Orr.

“I’m certainly not interested in clamping down on students’ rights to write about the things they are interested in, but I do think as the principal of the school I have the responsibility to be able to work with [the newspaper staff] to deal with the perception we are building,” Mr. Orr said.

According to PLD Lamplighter adviser, Mrs. Wendy Turner, Mr. Orr required that the staff provide “prior review and restraint” to him before he would allow them to go to the press. In 2009, the PLD Lamplighter was still a print newspaper.

“While it is within an administrator’s right in Kentucky to scrutinize the content of a student newspaper, in my opinion, the enforcement of prior review is an infringement,” Mrs. Turner said. “There were many times the students at that time had to rewrite stories or scrap them altogether.”

Journalism students in Kentucky may not have won greater protections in 2009, but there is a movement to try again.

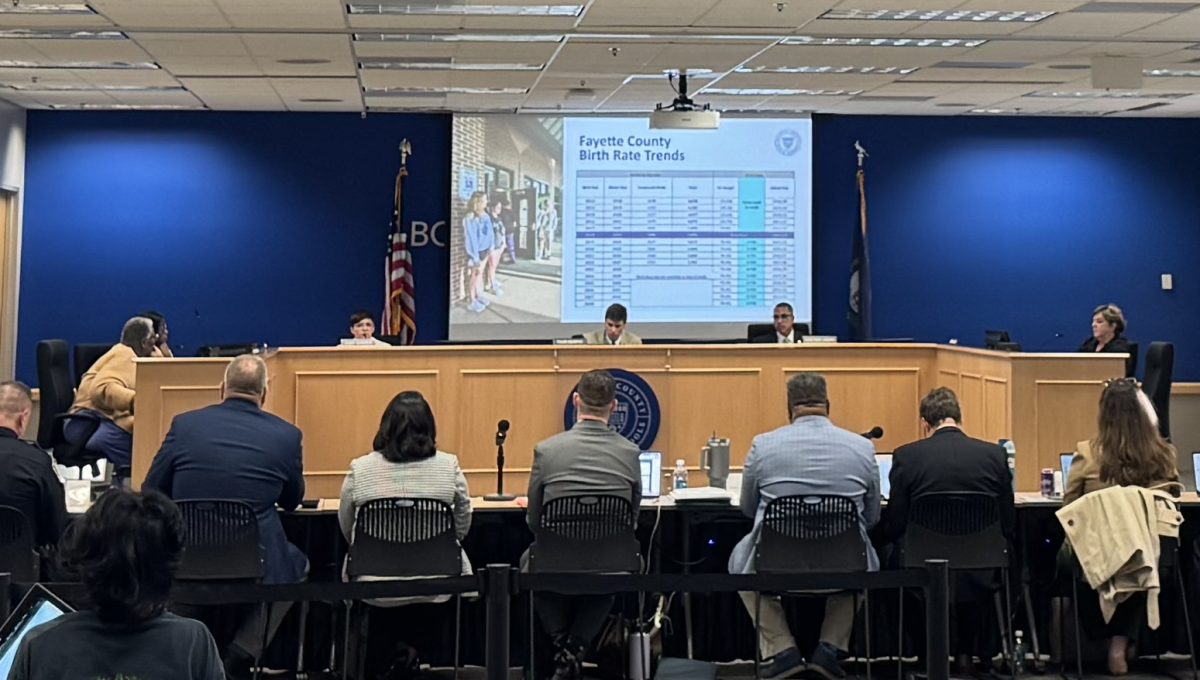

On Jan. 31, a discussion panel was held at DuPont Manual High School in Louisville to initiate the process that can pass the legislation for New Voices. Student journalists across the state attended along with Representative Attica Scott (D), First Amendment attorney Jon Fleischacker, and others invested in student journalism and students’ right to a free press.

“When you try to exercise your First Amendment rights to deal with issues in your school, and even your community, they become a threat, and that means you are doing a good job,” Fleischacker said.

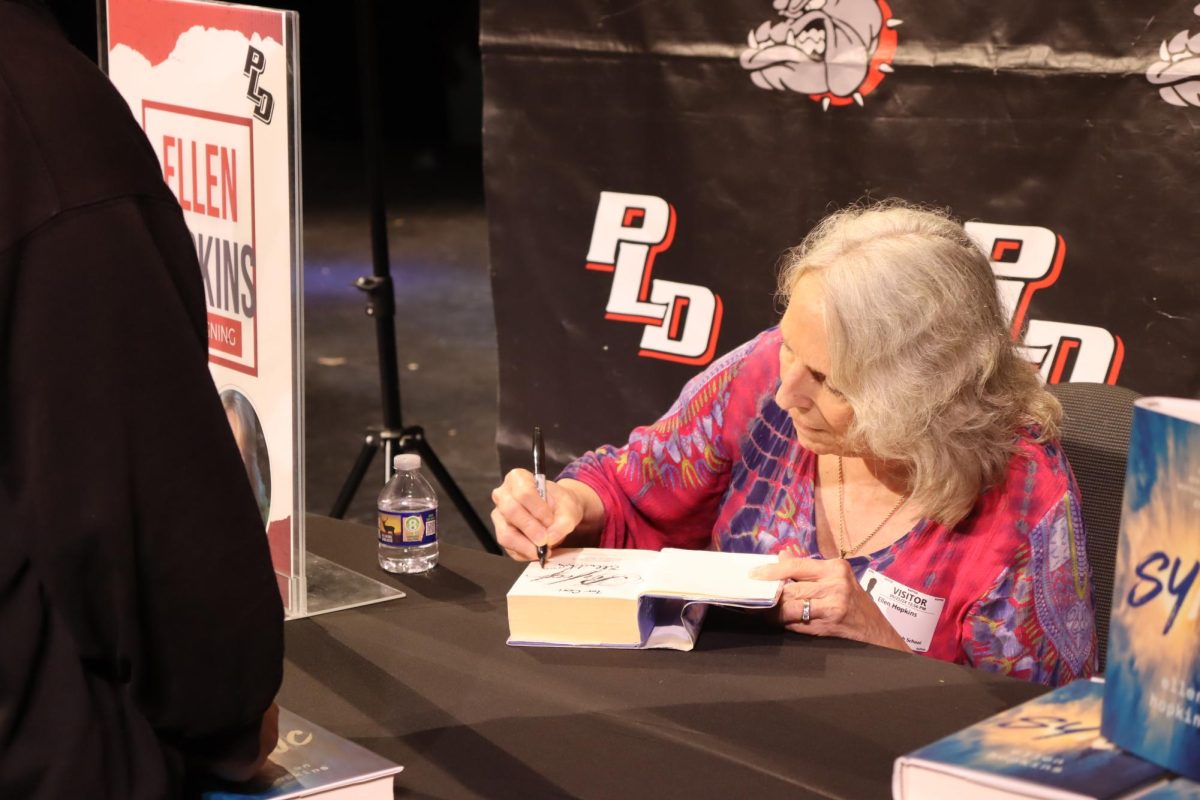

Also at the panel, Dupont Manual alum Emily Miles shared her experiences with censorship.

In 2009, Miles wrote a story about LGBT students on campus. She got permission from the parents and students involved in the story, but administrators of the school refused to allow her to publish the story. They published it in the yearbook anyway. Once the yearbooks containing the story came out, she said that she and others had to cut the article out of all 1, 200 copies with an X-Acto knife.

“That’s a tragic experience,” Miles said. “You work on this publication, you write your story, you finally get to represent your student body in a way that feels like freedom and justice, and then you have to cut it down the middle with a knife.”

Several other students involved in journalism programs across Kentucky contributed with their opinions on student censorship.

“Censorship in itself should be a story. Silencing student voices is an issue on top of the issues that they are covering,” DuPont Manual RedEye staff reporter Norah Wulkopf said.

“An ideal student newspaper is giving a voice to the voiceless and power to the powerless. It shouldn’t be hiding behind a facade, pretending to be perfect. It should be telling what’s wrong, pointing out what needs to change, and sharing opinions from every side,” PLD Lamplighter Sports Editor, Mike Marshall, said.

In Virginia, the New Voices bill was heard by the House Education Subcommittee. The bill, which was co-sponsored by state delegates Chris Hurst and Danica Roem, who are both former journalists, was introduced in November 2019.

“If we trust students to use a lathe in a woodshop or a blowtorch in a technical education course, why are we so afraid of giving them a pen?” said Hurst.

The bill was proposed in Virginia after a staff reporter from The Lasso at George Mason High School, Kate Karstens, wrote an article about the many absences at her school. About an hour after the article was published, Karstens received an email from her principal demanding that she take the article down.

“I actually remember having this physical response of rage–it was this pain, right below my collarbone,” Karstens said.

On January 29, deemed as Student Press Freedom Day, there was a hearing for the proposed law with the House Education Subcommittee. The bill, which states that it “grants student journalists in school-sponsored media at public middle, high and higher education institutions the right to exercise freedom of speech and the press, “did not go through the House Education subcommittee with a final vote of 5-3.

In New Jersey, the New Voices legislation was first introduced in 2015 but is only just now making a comeback with arguments in both chambers. The bill was introduced on the first day of the 2020 session.

Other states, such as Nebraska, also proposed the New Voices legislation. Senator Adam Morfield, who as a student journalist faced censorship in high school, sponsored the bill.

“It is essential that young student journalists in Nebraska have constitutional and statutory protection against censorship so that we build a new generation of journalists ready to inform others and strengthen our democracy,” Morfield said.

Student journalists across the United States are hopeful that legislators will recognize that their voices deserve to be heard.

“Every voice has a story, every person has a story to tell, and because of censorship, not every story gets well-represented,” said Marshall.

Hi! I’m Ella Williams, a senior at Dunbar and one of the Editors-In-Chief of PLD Lamplighter. I focus on our weekly broadcast, WPLD. I have been in this...

I'm Ella and I joined PLD Lamplighter as a freshman. This is my fourth year on staff. I have worked on editing and producing segments for WPLD, writing...

Marian Davis • Feb 17, 2020 at 10:05 PM

I like jovial commentary in a newspaper.. Could one of your writers please comment on the likeliness of two Ellas being on the contributors from the same school year? In fact names from the same year would be a great article.