Students, Policymakers Call for African American Studies

Recent protests against police violence have encouraged a reevaluation of how schools teach Black history.

As many students take to the streets to protest police violence, two Dunbar graduates have taken a different approach: addressing how racism impacts school systems.

Kaden Gaylord and Olivia Geveden, graduates of Dunbar’s class of 2018, have started a petition “to make ‘African American Studies’ a course offered at each public high school in the district.”

The petition was inspired by a thread Gaylord posted on Twitter on May 29 questioning the lack of education on African American history in high schools.

“I’ve been thinking about how our kids and grandkids are going to learn about this stuff,” he wrote. “The only subjects I was taught in school related to African Americans were slavery, civil rights, and Obama… Why have I had to learn white European history since the first grade and my history is taught as an elective in high school?”

Gaylord, now a student at Western Kentucky University, believes that teaching African American history is important to understanding the current protests against police violence.

“With everything that’s been going on, it would help everybody tremendously if they understood where we’re coming from and our history,” he said. “A lot of people think that there is no police brutality problem in America, or that the system isn’t built against African Americans. But there’s plenty of history that shows that there is.”

“As a Black man, you can get a 20 year nonviolent drug charge for marijuana, and nowadays you can have a white person capitalize off marijuana and make it into a million-dollar business,” he continued. “There’s a lot of injustice that I think people don’t understand or see.”

After seeing Gaylord’s tweet, Geveden, who knew Gaylord in high school, realized she’d had a similar experience.

“It wasn’t until I got to college that I was educated about these issues: the intersectionality of race, privilege, and implicit bias,” Geveden, who is now a rising junior at American University, said.

She reached out to Gaylord, and together they drafted and posted a petition on Change.org.

The petition was shared widely on social media, including by the PLD Seniors 2018 Twitter account.

As of June 12, over 17,200 people had signed the petition.

This far exceeded the pair’s expectations.

“Our original goal was only 12,300,” Geveden said, “because that’s the number of students enrolled in a public high school in Fayette County.”

Now that the petition has been signed by so many people, Gaylord and Geveden have started researching exactly how such a policy could be implemented and what changes would need to be made to the existing curriculum.

According to their course directories, Tates Creek and Dunbar already offer classes in African American Heritage, while Lafayette and Henry Clay offer African American Literature.

Frederick Douglass does not appear to have any courses relating to African American studies, and Bryan Station did not have a course directory available online.

At a statewide level, the Kentucky Academic Standards for Social Studies outline the minimum standards students should learn from kindergarten through high school.

In elementary school, students in third grade are supposed to learn about “interactions between groups of people in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania.” Fourth graders receive instruction on the African slave trade, and fifth graders learn that “certain groups, including women, African Americans and American Indians, did not receive equal rights or representation.”

The standards expand on these topics in middle and high school. For example, they suggest that teachers discuss the West African empires of Ghana and Mali with their seventh grade students.

Because many FCPS schools already offer some version of African American studies, and because the state does not have many specific curricular requirements regarding African or African American history, many people think these topics should be incorporated into required social studies classes, not just offered as electives.

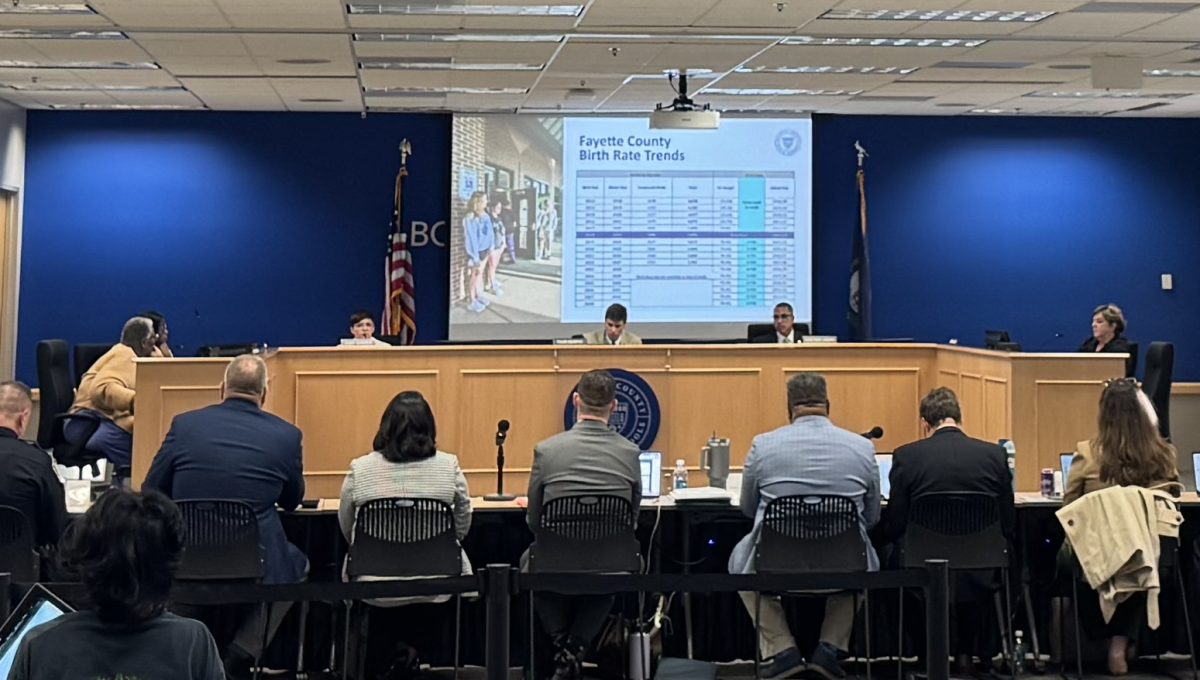

Tyler Murphy, an FCPS School Board member and social studies teacher, has called for a “Social Studies curriculum working group” comprising community leaders, teachers, students, and families. The group would work to identify ways to integrate standards on social justice and systemic discrimination into Fayette County schools.

“How can we make this something that isn’t just added onto what we already do, but incorporated into what we do at every level?” Murphy said. “I think that these are relevant conversations to be having across disciplines and grade levels.”

Murphy plans to present his proposal at the next FCPS School Board meeting.

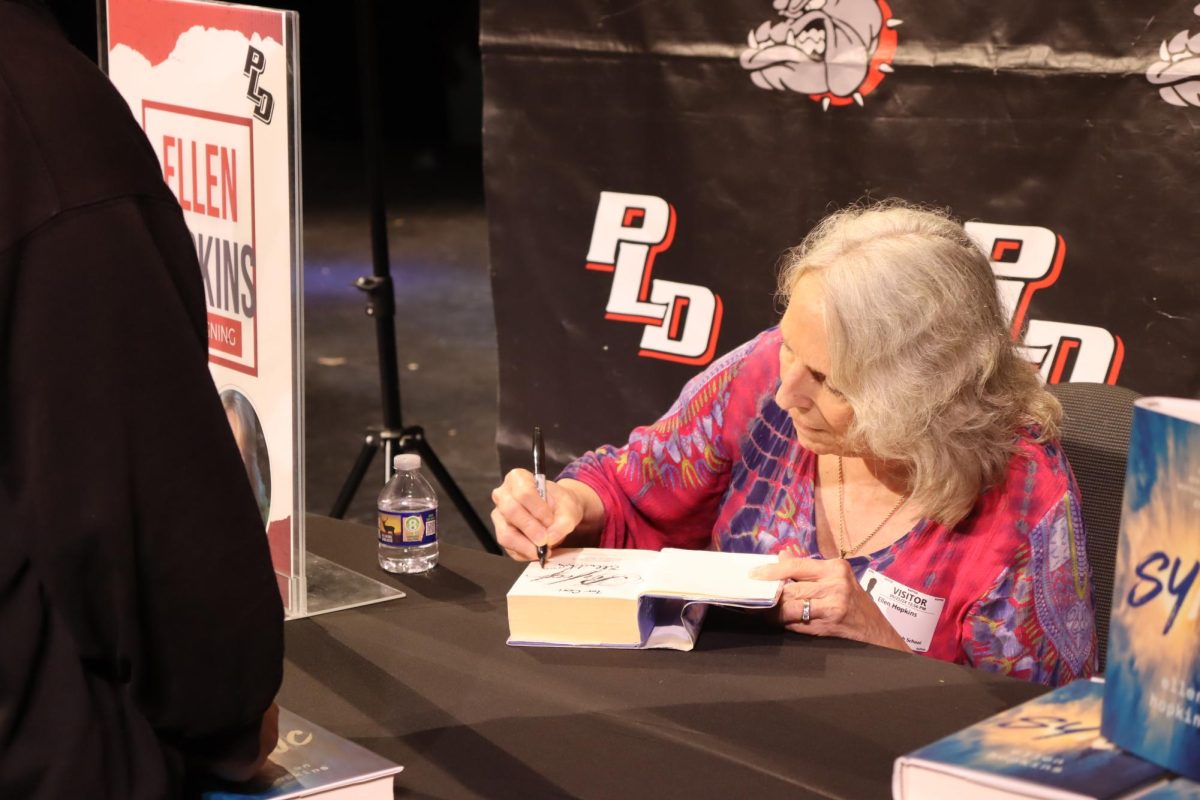

State Representative Attica Scott (D-Louisville) has made similar arguments in the state legislature. Last year, she pre-filed a bill to require instruction about African and Native American history in Kentucky world history and civilization courses.

“I know how important it is for all students to have this kind of education that goes beyond African American history beginning at slavery or Native history beginning at colonization because it boosts self-esteem, it boosts educational attainment and it provides for a more holistic world view,” Scott said.

Including African history in the core curriculum would also address concerns that students might not enroll in an elective course about African American studies.

Although it is included in the course directory, African American Heritage has not been offered for the past two school years. In the 2019-20 school year, 17 students requested the class, and in 2018-19, 11 students requested the class.

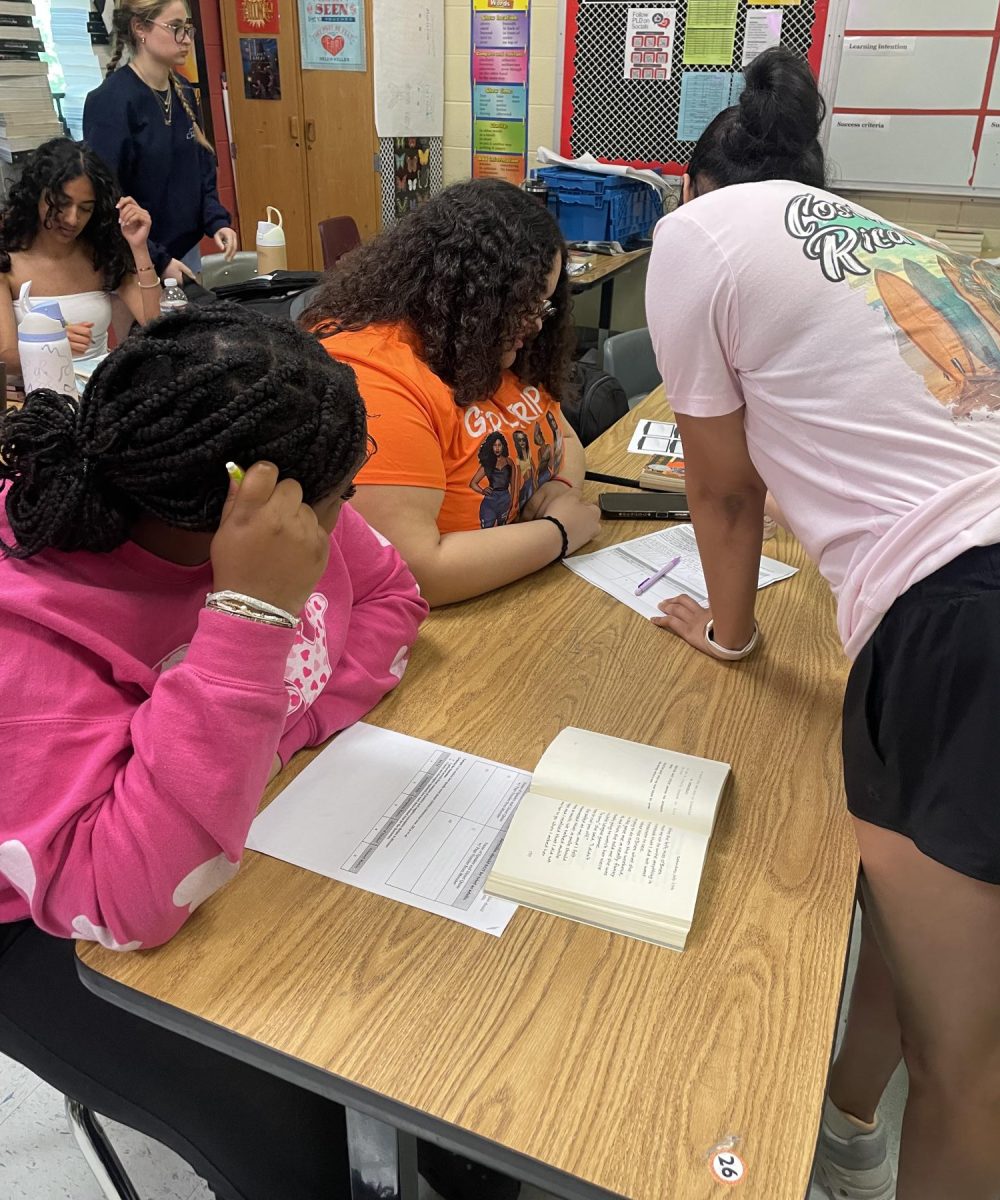

Dunbar’s Hip Hop as Literature course is also not being offered this year because only 17 students signed up, according to English teacher Amanda Holt.

She speculates that this decrease in enrollment might have been caused by “the creation of other new, interesting electives” or the “increased focus on pathway classes for students.”

Holt believes that “instead of relegating Black history and heritage to elective courses, we teachers, especially we white teachers, need to do some major reflection and work to decolonize our curriculum in our core content classes.”

However, Holt also said that “there is an interest in courses focusing on Black history and heritage.”

In prior years, both African American Heritage and Hip Hop as Literature have been requested by over 40 students.

Gaylord agrees that African American studies should “eventually [be] a graduation requirement” and that it should “be implemented throughout the US history and social studies curriculum.”

But like Holt, he thinks that “a lot of people would sign up to take it without any sort of push.” In the comments left on the petition, “everybody was like, ‘Oh, I wish I could’ve taken this class’ or ‘I wish I did this at Dunbar,’” he said.

Although there are many different groups taking different approaches to the inclusion of African American and African history in schools, they all share similar outlooks on the importance of education in achieving racial justice.

“I just want my city to do better and become better,” Gaylord said. “I think this is the first step in leading us that way.”

Hi! I’m Sadie Bograd, and I’m a senior at Dunbar. This is my second year on Lamplighter staff. I’m now one of the program’s Editors-in-Chief. Along...