International Crisis in Syria

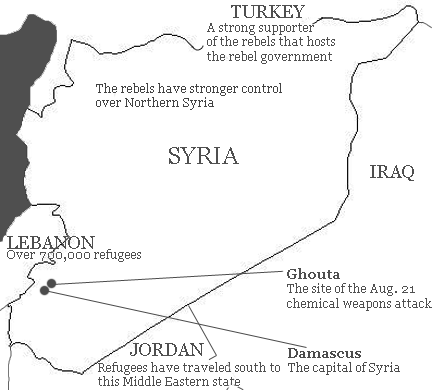

President Obama announced in early September that the United States would seek intervention in Syria amidst the supposed use of chemical warfare by the forces of Bashir al-Assad, the President of Syria.

In response to this movement, nations such as Russia and China soon began to threaten a military response to any American intervention, triggering a discussion about just how much risk the United States should take in Syria.

This discussion was intensified by President Obama’s decision to avoid pursuing immediate military action, instead seeking a Congressional resolution. This triggered a number of reactions from several members of Congress.

Opponents to the measure often cited the war-weariness of the American public and question the value of intervention to American security.

“Americans by large majority want nothing to do with the Syrian civil war,” said Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky in a press release. “There is no clearly defined mission in Syria, no clearly defined American interest.”

Meanwhile, those who supported the authorization of force cited humane reasons.

“The images of that day are sickening.” said Senator Menendez, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, during a hearing on the resolution. “In my opinion, the world cannot ignore the inhumanity and the horror of this act.”

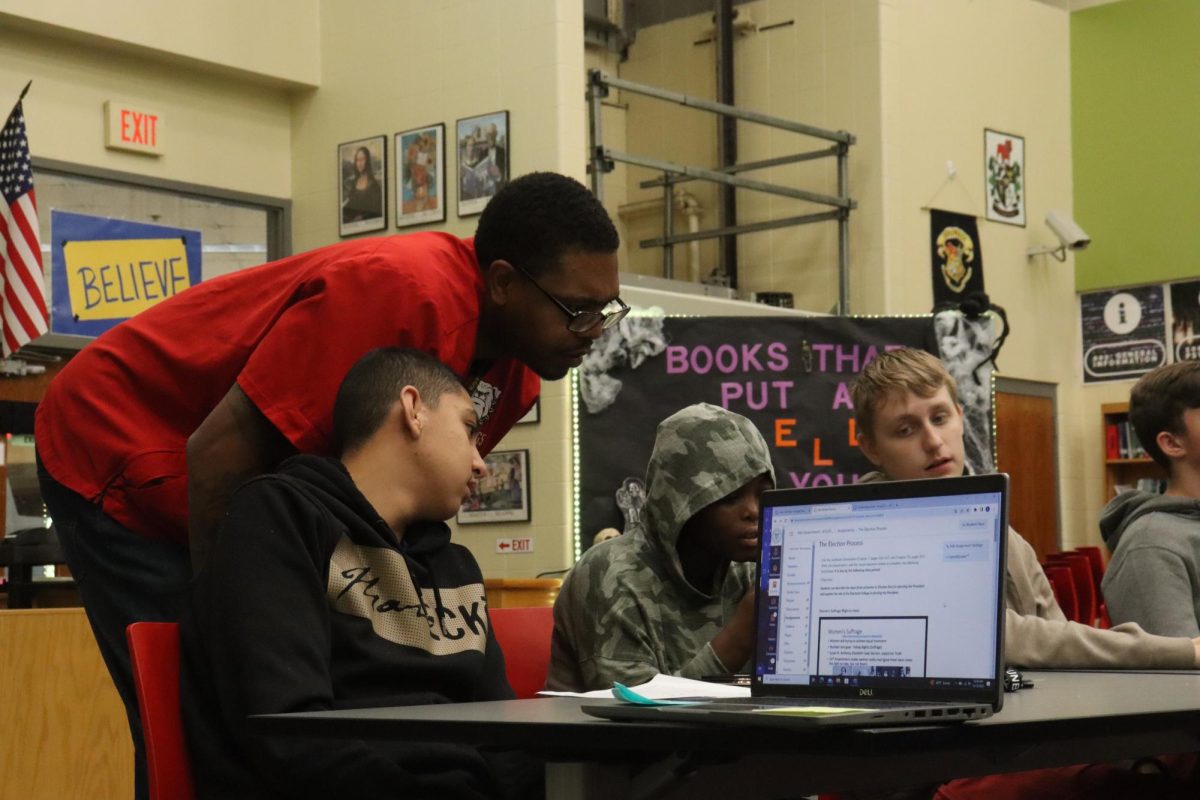

These attitudes about Syria were mirrored by some of Dunbar’s students.

“I don’t think we should go to war,” said senior Taylor Hudson, in opposition to America’s participation in the Syrian conflict.

Junior Daniel Ma, however, seemed willing to support a strike by the United States.

“If it is proven Syria used chemical weapons, we should consider launching military strikes,” Ma said.

Others had more expectant views.

“We’ve seen this stuff before. We should have a resolution,” said Dunbar senior Sergio Sanchez.

As congressmen debated the measure, President Obama reportedly encouraged them to view visual evidence of the August chemical strikes.

No doubt adding to this discussion, more than two million refugees have been forced to flee Syria by reports from the United Nations.

The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs expects that more than three million Syrians will be refugees by the end of 2013, and that eight million will require humanitarian assistance. Many refugees will be children, who face limited educational opportunities.

A report by Aljazeera in September estimated 70,000 children are working on the streets in Lebanon, a neighbor of Syria, while around 34,000 were enrolled in schools around the nation.

Antonio Gutteres, High Commissioner for Refugees with the UN, held this in mind when he commented on the tragedy, calling it “a disgraceful human calamity” that had caused “suffering and displacement unparalleled in recent history.”

This sense of urgency for the future of the Syrian state has given the current alternative, involving the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, focus on an international level.

First presented by Russia as an alternative to American military action, the response is seen as more diplomatic.

“This initiative has the potential to remove the threat of chemical weapons without the use of force,” President Obama said, promoting optimism for the plan.

Only time will tell if this plan will yield success as Syria begins the long process of disarming its chemical weapons.

“It’s a very technical operation,” President Assad said in an interview with Fox News. “[But] we want to fully cooperate with this agreement.”