According to the Global Gender Gap Report (2023), women comprise only 29.2 % of the STEM workforce.

Dunbar’s Math Science and Technology Center (MSTC) accelerates students interested in STEM to higher-level classes. While this acceptance in this program is test-blind, the class of 27’ is 70% male-dominated.

According to engineering teacher Mrs. April Gonzalez, 85% of all Dunbar engineering students are male.

“I have classes with 30 kids, but only two or three girls,” she said.

These statistics raise the question: how can we bridge the gender gap in STEM?

While the answer to this question has many layers, the first step is addressing the root of the problem.

It all begins with societal expectations, culture, and stereotypes.

Senior Sara Castillo wants to pursue forensic science after high school.

“I have experienced people dismissing my career choice or making it seem silly or an unrealistic job because of it being in the forensic field which is more female-dominated,” she said.

Historically, women were expected to stay at home and take care of the family.

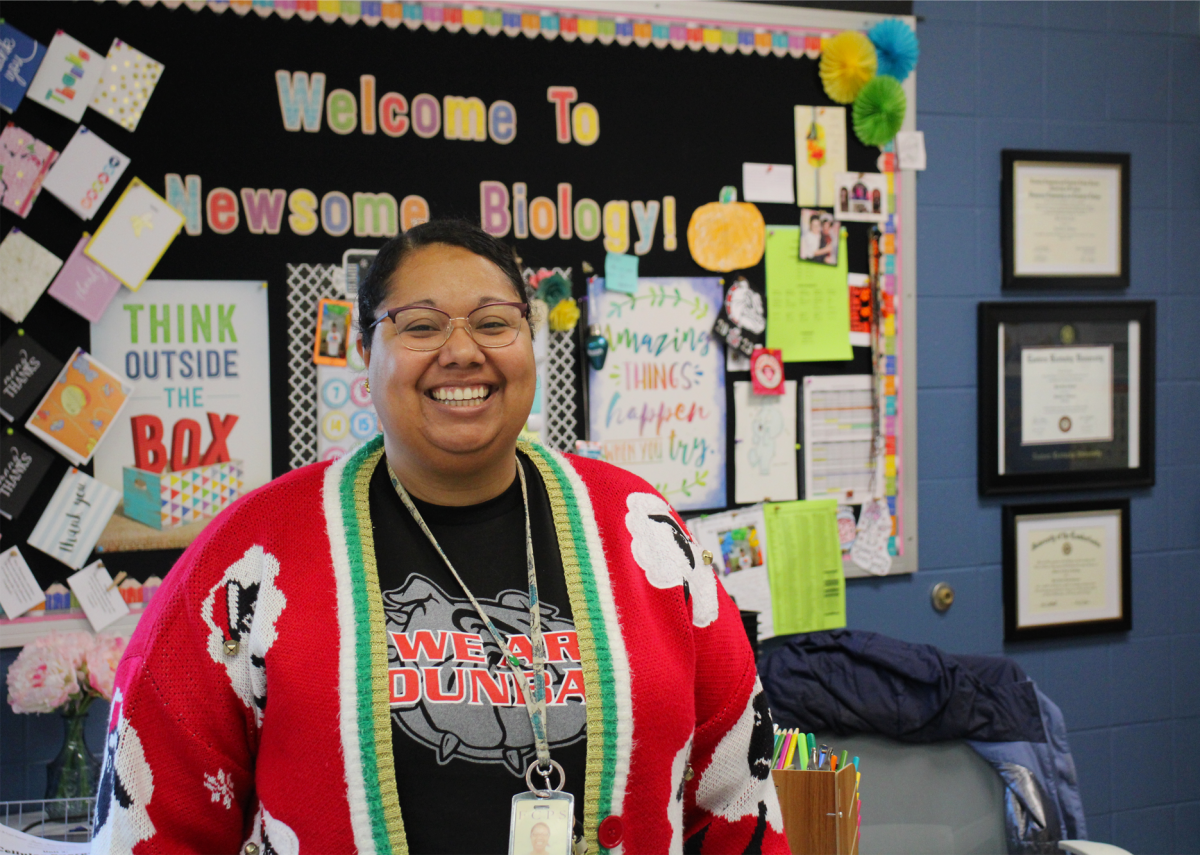

“The societal pressure of finding society’s unspoken roles can feel pressuring for women, which is why they may not go into careers that take longer to build, like STEM,” science teacher Mrs. Keia Scott-Newsome said.

As time has passed, women have fought to make a place for themselves in society, yet still face inequalities today.

“There is a negative connotation to a woman who is more independent because in society females are more submissive, so society wants females to go into more nurturing, submissive jobs, ” Mrs. Newsome said.

Certain communities and cultures may enforce these stereotypes.

Math teacher Mrs. Mary Moore talked about some “ extremely bright young women” who, when asked about furthering their education, said, “Women in [their] culture don’t go to school, [they] start taking care of the family.”

These beliefs may begin with assumptions.

“A lot of the time, everyone just assumes the girls aren’t as smart [as the boys],” MSTC junior Sophia Staples said.

These assumptions, starting as early as girls’ childhood, can play a large role in the way a girl may view STEM fields and possible opportunities.

“Girls often underplay their own intelligence starting around puberty in middle school,” Mrs. Gonzalez said.

“I feel like since girls feel like STEM is male-dominated, they don’t have confidence, even though they are often outpacing their male counterparts in math and science.”

These assumptions and beliefs can affect the women who are pursuing careers in STEM.

“Women who are pursuing STEM careers may start to doubt their ability to succeed in their careers which may put them behind men, who in fields such as engineering or computer science, are hired at higher rates than women with similar qualifications, “ said senior Sara Castillo, who will be pursuing forensic science in college.

Mrs. Newsome and Mrs. Moore said that they think confidence is something all girls need to have, especially those who are going into STEM.

“You could either be the loudest voice in the room or you can get drowned out,” Mrs. Newsome said.

“You have to know how to hold your own.”

“In females, when that confidence grows, they only do better,” Mrs. Moore said.

All teachers, Mrs. Newsome, Mrs. Gonzalez, and Mrs. Moore, said they did not have female role models in STEM growing up.

“If I had seen more women in STEM fields, that would have been a career path I would have at least considered pursuing, “ said Mrs. Gonzalez, who spent three years of college studying political science before pursuing STEM.

There is a lack of awareness of opportunities for women.

Mrs. Newsome, who did not pursue teaching science until the age of 30, said that since she was from a small town, most students went into factory jobs and did not know about other career paths.

“It’s really embarrassing to know how old I was to know about different careers,” she said.

Girls having some type of exposure to STEM could be helpful.

“Connecting to women in STEM and making sure they are represented in terms of career connections and guest speakers is important when building diversity in the workforce so that everyone can see somebody they connect with and can see being successful in that field makes them feel more open to seeing that there is something there for them.”

Castillo also agrees.

“I think that exposing young girls to a variety of careers in STEM (not just the classic STEM careers like engineering, computer science, biology, etc.) can show young girls that STEM has so much to offer them,” she said.

Mrs. Newsome, however, said that she was often discouraged from pursuing certain things because of her color.

“I was told in college many times that I need to grab ahold of reality and hang on tight because school might not be for me,” she said.

Mrs. Gonzalez and Mrs. Moore believe that being more intentional is key to showing young girls they can be successful in male-dominated fields.

“I try to think of opportunities and role models specific to our girls and I try to have more conversations to make sure they feel comfortable because they are in very male-dominated classrooms,” Mrs. Gonzalez said.

Mrs. Moore said that encouragement for young girls is something that she tries to instill in her students, especially her female students, because of how important it is for her.

“I was encouraged early on that I could and was smart enough to do anything,” she said.

“If I didn’t have the support I had at home, I wouldn’t have gone on.”

In hopes of creating awareness and opportunities for students, Dunbar will be implementing the STEM+ program next school year with a biomedical pathway.

“I think it will draw a lot more inclusivity,” science teacher Mrs. Gilvin said.

“Don’t let people tell you can’t do things because you are a girl, ” Mrs. Gonzalez said.